Nature of the Issue/Problem

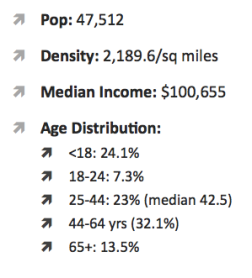

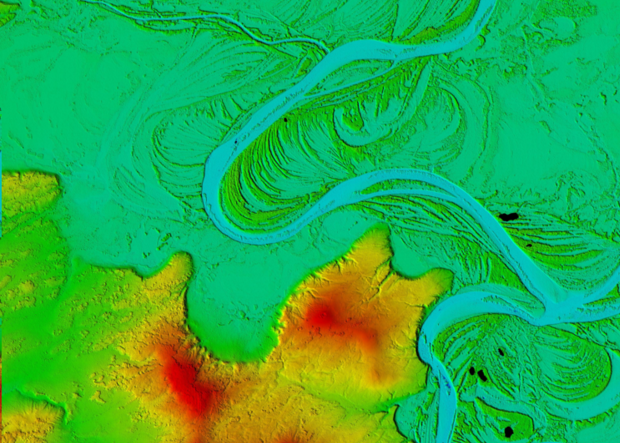

The freshwater crisis is an issue that most Americans are beginning to observe as a global threat that does not exempt any individual from its effects. Although underdeveloped countries experience the water crisis on a more substantial scale, the U.S. is not sheltered from the devastation that results from the misuse and lack of regulation of this essential natural resource. “The UN estimates that by 2025, forty-eight nations with combined populations of 2.8 billion, will face freshwater “stress” or “scarcity” (Water.org, 2008). Less than 1% of the Earths fresh water is potable or available for direct human use. Increased pollution and population growth are contributing further to the declining availability and quality of fresh water. New Jersey is the nation’s most densely populated state with 1,134 people per square mile, and according geospatial analysis it continues to grow at a rate of 16,600 acres per year (Hasse, 2003). This increase in sprawl is diminishing wildlife habitat and farmlands, as well as degrading water quality and environmentally sensitive areas.

Smart growth is a term to describe patterns of development that reduce the negative externalities created by sprawl. Some characteristics of smart growth include mixed land use, open space, farmland preservation, as well as community and stakeholder collaboration in decision-making (Hasse, 2003). Smart growth development was a method used to preserve The New Jersey Highlands region, which is significantly important to New Jersey as a water source for half of its population. Between 1995 and 2000 the Highlands lost 17,000 acres of forests and 8,000 acres of farmland, this growth continues to consume land at around 3,000 acres per year (NJ Highlands Council, 2007). Due to the population pressures in New Jersey, which posed the threat of increased degradation and sprawl, Governor McGreevy assembled the Highlands Task force in 2003 to acquire advice on a plan that would preserve the water in the NJ Highlands Region, while still allowing for economic growth. The Task Force concluded that a preservation area in the Highlands should be created in order to protect open space and the core of the region, which held the most vital and environmentally sensitive ecology. These recommendations set the stage for Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act, which restricted 350,000 acres in the Highlands from being developed further (New Jersey Highlands Council, 2007).

History

The New Jersey Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act is a comprehensive land use plan affecting eighty-eight municipalities that was passed under the McGreevey administration in August 2004 (ANJEC, 2010). The act’s environmental regulations supersede local laws of the eighty-eight municipalities contained within the Highlands Region and is instead strictly regulated by the state concerning land use and development to ensure consistency towards the goal of water protection. The New Jersey Highlands region is a 1,343 square mile region of northwestern New Jersey specifically noted for its environmental value, including its substantial water source, which over 5 million NJ residents depend on for clean water (NJ DEP, 2004). The Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act was provoked by the decline in undeveloped land area and subsequent degradation of environmental quality of the New Jersey Highlands Region. Dramatic and rapid increase in development over several decades stripped acres of forest and destroyed areas of wetlands (ANJEC, 2010). After a few decades of extensive development, the region was significantly degraded and its environmental quality diminished, affecting its natural resources – including water (NJ DEP, 2004). Increased fragmentation caused by suburban sprawl was also a major concern as it depleted habitats, vital resources, and disrupted the ecological balance of the entire region (ANJEC, 2010). The area also contains a diverse amount of natural resources including contiguous forestlands, wetlands, watersheds, and plant and wildlife habitats unique to the Highlands region (NJ DEP, 2004). Additionally, the Highlands region also contains historical sites, approximately 110,000 acres of active agricultural land, and creates recreational opportunities (NJ DEP, 2004).

The Highlands Region has an early history of faming due to the extremely fertile and productive low valley lands (New Jersey Highlands Council, 2008). Later, the region became a key area in ironworks after the discovery of rich iron oxide deposits (New Jersey Highlands Council, 2008). The natural resources of the region made the area successful early on, thus industrialization brought about a dramatic increase in population and subsequent development. Although some areas of the Highlands are still used for agricultural purposes, the area is not nearly as dominated by agriculture as it once was and is instead frighteningly overdeveloped. The significance of the region has been federally recognized for at least 100 years and throughout the last century, so individual municipalities allotted reservoirs and preserved open space. (New Jersey Highlands Council, 2008). Previous legislation has not sufficiently protected the land and water supply due to the expansive amount of real estate being controlled by seven different counties (ANJEC, 2010). Water quality steadily diminished as watersheds became increasingly contaminated and inconsistently regulated. The significance of the issue began to rise as water and land quality suffered under incompatible environmental standards and development/planning laws that each municipality had controlled. The need for a cohesive, comprehensive land use plan became intrinsically vital in securing the natural resources of the Highlands region.

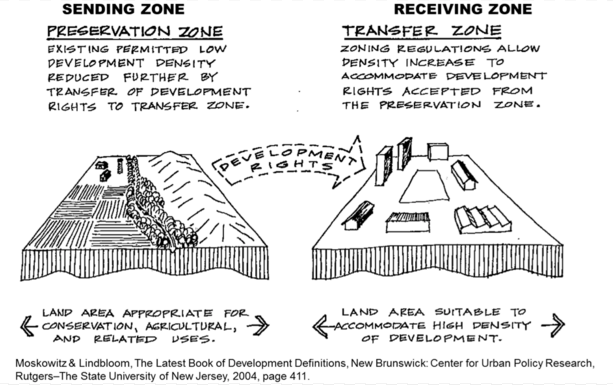

The New Jersey Highlands Act of 2004 divided the Highlands into two regions: the Preservation Area and the Planning Area (ANJEC, 2010). Greater development is allowed within the Planning Area and development is strictly prescribed within the Act. The Preservation Area is more sensitive to environmental disruption and therefore restricts and highly regulates development. Ultimately, protection of the region and outlines for responsible development were prescribed through legislation and enacted into law in 2004. After thorough analysis from the Highlands Council and a public review process the Highlands Council approved the Highlands Regional Master Plan on July 17th 2008, which then became effective on September 8th 2008. In addition to providing detailed regulatory procedures the Regional Master Plan included in depth technical assessments and information to assist municipalities in conforming to the stipulations of the Highlands Act. The Highlands Act mandates that local governments conform to the Regional Master Plan and adopt ordinances to implement those plans. The Master Plan also contained expansive guidelines for the Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) Program to address the equity issues of landowners. The establishment of a regional planning body, tighter environmental regulation, and TDR programs, although new to the Highlands, have precedents in earlier Legislative action by the state of New Jersey.

The government of New Jersey has taken action on environmental quality standards and development even before the New Jersey Highlands Act. On two other accounts, the Meadowlands and Pinelands of New Jersey both inspired acts of legislation as environmental concerns arose after irresponsible development. The Hackensack Meadowlands Reclamation Act of 1969 created the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission (New Jersey Meadowlands Commission, 2010) and the Hackensack Meadowlands Municipal Committee. The thirty-mile area of the Meadowlands was previously regarded as a dumping ground, polluting that Hackensack River and its marshes and corresponding watersheds (New Jersey Meadowlands Commission, 2010). The NJMC’s mission was to restore the Meadowlands district, which had been long abused by illegal dumping and mistreatment of the land. The Meadowlands Commission is responsible for zoning and planning for the Meadowlands district while promoting economic growth of surrounding communities (New Jersey Meadowlands Commission, 2010). Similarly to the Highlands region, fourteen municipalities controlled the larger Meadowlands area separately. These municipalities created massive incompatibilities in regards to the regulation of pollution and land use (New Jersey Meadowlands Commission, 2010). Again, the State was pressured to intervene and establish a commission that was responsible for the comprehensive master plan of the region.

Another significant piece of legislation concerning the preservation of unique and necessary environments was the National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978. The New Jersey Pinelands National Reserve (1979) was created by Congress under the National Parks and Recreation Act. This identified the Pinelands region as sensitive and vulnerable to negligent development due to the habitats and resources that are found in the region (New Jersey Pinelands Commission, 2007). The Act established the Pinelands Commission, which is instated within the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection but operates without the supervision of the department, and called for a Pinelands Comprehensive Master Plan (New Jersey Pinelands Commission, 2007). In addition to defining the boundaries and habitats threatened by increased development, the act also prescribes limitations of development within the preservation area. The 1.1 million acres of land within the Pinelands National Reserve was nationally and internationally recognized as a Biosphere Reserve in 1983 and 1988 respectably (New Jersey Pinelands Commission, 2007). Similarly to the Highlands Region, the impressive amount of land protected under the Pinelands National Reserve is underlain by aquifers containing 17 trillion gallons of pristine water, making it an important water source and water recharge area (New Jersey Pinelands Commission, 2007). In addition to being a significant natural resource, the Pinelands National Reserve also contains historic value, economic and recreational opportunities, as well as sentimental cultural value. In 1967, the publication of “The Pine Barrens” by John McPhee sparks “tremendous public outcry to protect the Pinelands natural and cultural resources” (New Jersey Pinelands Commission, 2007). Public pressure to protect the region influenced the legislation decision to allocate the Pine Barrens as a preserved site. Like the Highlands, the Pinelands contains vital natural resources which have become victim of unconscious development and under regulated environmental standards when it was controlled by a number of municipalities. The federal and state response in the late 1970s finally designated the region an area of environmental importance and in 1979 Governor Byrne signed the Pinelands Preservation Act and later approved the Pinelands Comprehensive Master Plan in 1981 (New Jersey Pinelands Commission, 2007).

Actors Involved with the Highlands Act

The Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act affects millions of people every day, from regulating development to the quality of New Jersey’s drinking water. Since the policy has such a comprehensive power over millions of New Jersey residents, the act has an equally large amount of actors that are affected by the policy or who are involved with its implementation. The actors involved have a broad background, spanning from some of New Jersey’s farmers to the Highlands Council. This policy stands as one of the most significant environmental sustainability and development acts in New Jersey’s history. However, it is still experiencing issues regarding implementation seven years later. The policy is a point of contention because some actors are affected more negatively while others are affected more positively. This section will examine each involved actor and evaluate its power regarding implementation and their own personal agendas in the scope of the political sphere.

Arguably one of the most significant actors involved with this policy is the Highlands Planning Council. The New Jersey Legislature created the council to oversee the future implementation and enforcement of the act in 2004. There are fifteen seats on the council and the governor appoints all of the members. The Highlands Council was enumerated several powers by the NJ Legislature. This includes- developing a comprehensive Highlands Regional Master Plan, passed on July 17th, 2008; identifying areas within the preservation zone of the Highlands Region where development shall not occur; a limited authority to review and accept or reject building proposals within the Highlands Preservation Zone. The Highlands Council has developed an array of incentive to expedite implementation of the regional master plan to conforming municipalities. Those municipalities that do conform to the regional master plan are offered grants, legal assistance in case the municipality is sued, tax assistance, and the ability to engage in transfer of development rights. Those municipalities located wholly or partially within the preservation zone that do not comply with the regional master plan will meet legal action because by law they must be in compliance with the regional master plan, as well as having state funds withheld from them. Despite having several vacant seats and being shrouded in controversy, the Highlands Council has continued to approve municipal master plans that are in conformance with the regional master plan (NJ Highlands Council, 2007).

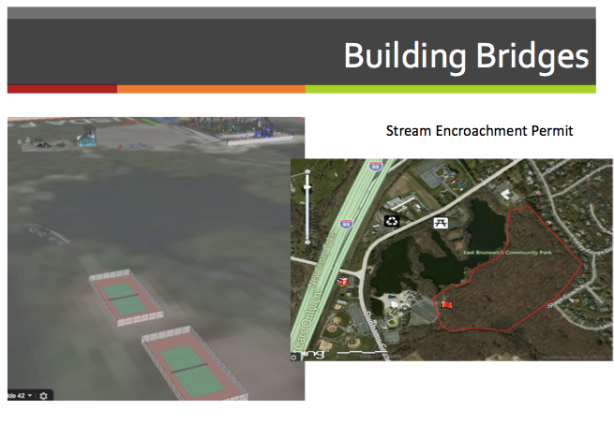

Another actor that works closely with the Highlands Council is the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, a state agency tasked with preserving the state and character of New Jersey’s environment. The NJDEP has its own set of rules and regulations that specifically pertain to municipalities within the preservation zone; these municipalities must comply with the NJDEP’s rules or else they will be met with legal consequences. If a proposed development lies within the boundaries of the highlands preservation zone and is defined as a major highlands development then the development may be regulated by the NJDEP. A “major highlands development” is defined as any non-residential development within the preservation area, any residential development that requires an environmental land use or water permit, or disturbs more than one acre of land. Any development that meets the criteria for a major Highlands development may be prohibited from developing within the Highlands Preservation Area (NJ Highlands Council). In recent news, the NJDEP and Highlands Council working against one another have undermined the Highlands Act. Specifically, the NJDEP approved a housing development in Huntington Knolls that the council had previously rejected. This sets a bad precedent and highlights the problem the council and NJDEP are dealing with – since two state bodies are arguing and second-guessing each other’s work (Stamato, 2009).

Opposite from the Highlands Council and NJDEP are the local government officials. These officials are composed of the mayor and councils, planning board officials, and freeholders of the 88 municipalities and seven counties within the highlands region (NJ Highlands Council, 2007). These officials have the responsibility of balancing environmental, political, and economic considerations. As a result of the restrictive nature taken towards development, many officials have voiced dissatisfaction with the current form of the Highlands Regional Master Plan, but most have complied with the master plan because of incentives offered by the Highlands Council. The officials, listening to their constituency, have raised concern over the Highlands Act’s ability to protect economic viability as well as environmental sustainability. In light of this, many officials have called for amendments to the act because for many municipalities, especially those within the preservation area, the cost benefit of compliance is too great to handle. This is so because ratables are being driven out to more development friendly areas and land values are being deflated because there has not been adequate funding set aside yet for the TDR program.

Voicing their concerns to local government officials has not been a problem for the property owners within the Highlands region. Many property owners, especially those within the preservation zone, have strongly objected to the Highlands Act. This is so because some landowners have not received just compensation for property devaluation stemming from landowners not being able to develop their properties and because ratables that would be received by business are leaving the highlands. Property owners within the planning zone have voiced less opposition to the policy but there is still objection (O’Connor, 2010). Some property owners do not want to diminish the rural character of their land that would stem from the development of a receiving zone adjacent to their property and other landowners do not want to incur new costs that would materialize from the large infrastructure projects that would accommodate new developmental growth in the receiving zones. Although many residents like the idea that they are taking steps initiative to protect the water for themselves and future generations, many landowners stand to lose something. As a result, many of the affected landowners have petitioned the government to repeal the act, albeit so far it has been unsuccessful.

In addition to the power of individual landowners to seek agenda change and alternative specification, advocacy groups have also exerted their influence the Highlands Act. The most prominent advocacy groups involved are The NJ Builders Association, NJ Future, and the New Jersey Chapter of the Sierra Club. The NJ Builders Association has been very critical of the act because it limits the ability to develop in areas of the state. They also oppose it because the TDR program has not received sufficient funding to compensate households and towns that have experienced a decrease in property values. NJ Future and the Sierra Club both support the act, but both are critical over the act’s abbreviated ability to protect the Highlands because of budget cuts stemming from Governor Christie. Now that the Regional Master Plan has been passed, the groups have tweaked their strategies and now have focused on trying to amend the language of the regional master plan to support either a more comprehensive protection of the environment – NJ Sierra Club – or support developmental interests – NJ Builder’s Association (Horowitz, 2011). Whatever the outcome will be, all of the advocacy groups listed have voiced their concern that the Regional Master Plan falls short of its goals to adequately protect the drinking water and/or the right of individuals to develop.

The time between the 2004 Highlands Act to the passing of the Regional Master Plan in 2008 has seen great change in the political arena. The officials that encompass the Highlands Council all had a voice in passage of the Regional Master Plan in 2008. Since the Governor appoints the council, in the time spanning 2004 to 2008 we have had three politically polar governors -Governor McGreevey, Governor Corzine, and Governor Christie, which is shown in the voting behavior of the council. Regarding the passage of the Regional Master Plan, with one vacancy, the fourteen-member council voted 9 to 5 in support of the Regional Master Plan. Among the five that voted against the RMP were: Council members Tracy Carluccio, Debbie Pasquarelli, Tim Dillingham, Kurt Alstede, and Glen Vetrano. These five members voted against the plan because they felt that the current state of the plan was either too lenient on environmental regulation or too stern regarding development (Horowitz, 2011). The other nine council members that voted in favor of the Master Plan, stated that they did so because they felt they were taking adequate steps to protect the Highlands. The voting behavior of the council reflects the values, both political and ideological, that the council members possess and whether they value economic viability or environmental sustainability more.

In light of the actions of the Council, it is important to address the case of Mansfield Township, the only non-conforming municipality. Just as Kurt Alstede and Glen Vetrano voted against the master plan because it didn’t protect the interests of landowners and development, Mansfield Township has chosen not to conform to the council’s Regional Master Plan. Mansfield is obligated by law to conform to the Master Plan because they are within the preservation zone, but they have chosen not to do so because the mayor, town council, and residents of the municipality feel that land price would be artificially devalued without compensation. As a result, the State of New Jersey on behalf of the Highlands Council has chosen to withhold thousands of dollars in funds owed to the municipality and will not give them up until Mansfield Township complies (Stamato, 2009). Whether Mansfield Township will continue to be nonconforming is yet to be determined. All 87 remaining municipalities in the Highlands have opted to comply with the master plan, even those municipalities within the planning zone where compliance is discretionary, because of the incentive plan offered by the council and are now in the process of having their municipal master plans be in accordance with the regional master plan. Conforming towns can look to receive tax assistance for lost ratable base, legal representation, grants, and the future benefits of the TDR.

Perhaps the most vocal group of people in opposition to the act have been local farmers in the preservation area. These farmers have petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to hear their case against the Highlands Act. The reasons for the farmer’s disgust over the act is similar to many other homeowners in the Highlands region, they feel that the act unjustly lowers their property values because they cannot develop the land (O’Connor, 2010). As a result nobody would like to buy the farm land they cannot develop. In addition to the farmers, Republican Governor Chris Christie has been a vocal critic of the Highlands Act. In light of record state debt, the Governor has taken a hard line against state discretionary spending. As a result, Governor Christie decided to cut the operating budget that the Highlands Council uses to offer incentives to complying towns as well as a source of funds for enforcement.

The amalgam of actors involved with the Highlands Act represents a heterogeneous background. Each actor has its own personal agenda regarding the Highlands Act. As a result, the involved actors are all trying to influence the act in such a way that will reflect upon their interests most favorably.

Implementation of an Incomplete Plan: The Transfer of Development Rights Program

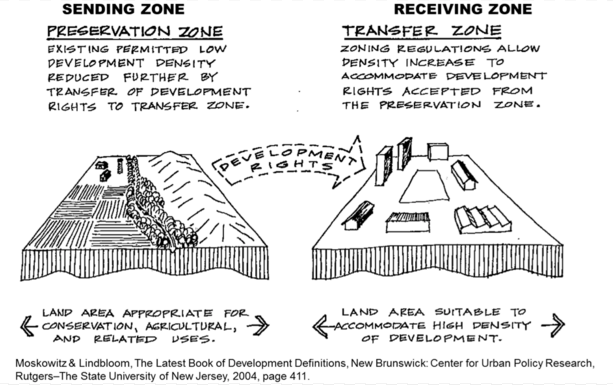

The Transfer of Development Rights (TDR) Program is a crucial component of the Highlands Act. Without it, the Act would potentially represent a politically and legally untenable scenario that would constitute an unjust taking by which property owners are stripped of the equitable value of their land. The TDR Program designates eligible properties as Sending or Receiving Zones. The value of eligible property in the Sending Zones is converted into Development Credits, which are then purchased by developers in Receiving Zones to increase the allowable development capacity of their property. The Highlands Development Credit Bank is a third party under the oversight of the Highlands Council that serves as a broker and initial financer of transfers of Development Credit. Unfortunately, the importance of the TDR program has not led to sufficient funding of the program, a situation that critics of the Highlands Act have been quick to seize upon. Nonetheless, the TDR Program has had initial success in its first phases of compensation for Preservation Zone property owners.

Sending Zones consist of properties in the Highlands Preservation Area that meet specific eligibility criteria. Properties can be residential or non-residentially zoned. The land be must be situated in designated Protection or Conservation Zones. A parcel of land also must be at least five acres and three times the minimum lot size. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the land must be undeveloped. Additionally, property owners of land that does not meet these stipulations can request a special determination of eligibility from the Highlands Council. (New Jersey Highlands Council, 2008)

Once a property is deemed eligible, the development value of the tract of land is converted into Highlands Development Credits (HDCs), which can then be allocated to property owners in the Receiving Zone. Once the land’s value has been converted to HDCs, a restriction preventing development is placed on the deed to the land. In order to account for the fluctuations in property value between the various regions of the Highlands, the HDC was created to be a unit of monetary exchange between property owners according to a formula (Appendix B) that scales the net yield of a tract of land according to property value and potential uses had the land been developed (New Jersey Highlands Council, 2008). The Highlands Council has set the initial value of HDCs at $16,000 per credit. However, once the private market for HDCs has been established, the price is expected to fluctuate according to demand (Highlands Council, 2010). Once allocated, HDCs can then be sold either to the Highlands Development Credit Bank or to private landowners in the Receiving Zone.

Receiving Zones consist of tracts of land that have been designated as such by their municipalities and approved as conforming to the Regional Master Plan if they are within the Highlands or the general State Planning Commission guidelines for municipalities outside the jurisdiction of the Highlands Act. To obtain such designation, municipalities must complete a feasibility assessment before petitioning the Highlands Council for designation, and then prepare a Transfer of Development Rights Ordinance for review and approval by the Highlands Council (New Jersey Highlands Council, 2008). Initially, only municipalities located in counties that were located in the Highlands region could apply for TDR designation. However, the 2010 signing into law by Governor Christie of the Highlands TDR Extension Bill (A602/S80) gave any New Jersey municipality the option of petitioning for Receiving Zone designation (Highlands TDR Extension Bill, 2010). Receiving Zones within the Highlands region can be designated as Higher Intensity Receiving Zones if they contain the infrastructure to allow density of over five dwelling units per acre or Lower Intensity Receiving Zones for communities that are more rural or suburban in nature and cannot accommodate residential density of five dwelling units or more per acre (New Jersey Highlands Council, 2008).

Despite the enactment of the TDR Program with the 2008 approval of the Regional Master Plan, a great deal of uncertainty remains over the financial viability of the program, leading to criticism from opponents of the Highlands Act. Initially, the TDR market was expected to be completely private. Consequently no funding was allocated to the TDR Program when the Highlands Act was enacted, leading state Senator Michael Doherty, among others, to attack the plan. According to Doherty, “There is no foreseeable plan to provide compensation to landowners who see the development potential of their land being taken away” (Robbins, 2009). Despite such bruising political rhetoric, the fact of the matter is that in issuing Executive Order 114 in September of 2008, Governor Corzine provided $10 million in initial funding to the HDC Bank for the purchasing of development credits (Executive Order 114, 2008). As of April 2011, $2.596 million of that initial fund has already been used to purchase HDCs from nine property owners (Garretson, 2011). For Doherty and other critics though, the seed money seems wholly insufficient as a means of compensating property owners in the Highlands. Indeed, a weakness of the program appears to be the need for developer demand to reach sufficient levels to create a sustainable private market for development credits (New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station, 2011).

The Transfer of Development Rights Program is an essential facet of making the Highlands Act a viable and equitable solution to the regional planning goals of northern New Jersey. Providing compensation to landowners for the lost value of their property represents a vital step in ensuring that growth in the region is redistributed in a manner that does not create an unfair hardship to property owners. However, controversy over the program and its lack of funding has given the Act’s opponents the ammunition they needed to increase their criticism. Even after a short term solution was enacted through Executive Order 114 to ensure the TDR program’s immediate viability, the critics have continued their attacks, since the $10 million that was allocated is still not enough to fund the entire program. For the TDR Program to be a long-term success, the growth and development of a vibrant private trading market in development credits must occur as soon as possible.

Legal and Political Challenges to the Highlands Act

As one might have expected from such a controversial piece of legislation, a variety of legal and political challenges have been mustered in opposition to the Highlands Act in an attempt to repeal, revoke, nullify, or otherwise weaken the Act. Highlands litigation has been pursued on all levels of the legal system, all the way to the United States Supreme Court. In every instance however, these attempts have been unsuccessful. The courts rejected legal challenges to the Highlands Act and a legislative attempt to weaken the act ultimately resulted in failure.

The most significant litigation that took place in state courts was the 2007 case OFP, LLC v. State of New Jersey. This case involved a challenge of the constitutionality of the Highlands Act by a Morris County developer who wanted to subdivide their property. The plaintiff argued that the Highlands Act “operates as a bar to development as otherwise permitted by law and results in a taking of OFP’s property without compensation” in violation of the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and Article I, Paragraph 20 of the NJ Constitution in addition to a violation of equal protection and due process guarantees (OFP, LLC v. State of NJ, 2007). The New Jersey Superior Court ruled against the plaintiff in January of 2008, and was upheld by the Appellate Court and also the New Jersey Supreme Court, which refused to hear an appeal.

Also notable was the litigation pursued by Warren County farmer John Kasharian in a petition before the United States Supreme Court. In Kasharian v. The Highland Act of New Jersey, Kasharian alleged in his petition for a writ of certiorari that the Highlands Act was a violation of the equal protection rights granted in the United States Constitution. Kasharian’s argument was based on the dubious suggestion that the State of New Jersey’s enforcement of Highlands regulations represented regulatory action that should only fall under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (Kasharian v. The Highland Act of NJ, 2009). The U.S. Supreme Court rejected Kasharian’s petition in June of 2010.

Prior to the aforementioned legal challenges was a legislative attempt to effectively weaken the Highlands Act by neutralizing the authority of the Highlands Council. Co-Sponsored by two of the Act’s most vocal enemies, Assemblywoman Marcia Karrow and then-Assemblyman Michael Doherty (both Republicans of the 23rd District), the so-called Highlands Improvement Act (A2915) would restore elements of home rule that had been removed by the Highlands Act. A2915 would create a board of elected officials from local municipalities to oversee the Highlands Regional Master Plan in an action that would strip a significant amount of regulatory control from the Highlands Council (Highlands Improvement Act, 2006). However, the Highlands Improvement Act died in committee and did not reach a vote (Highlands Improvement Act, 2006).

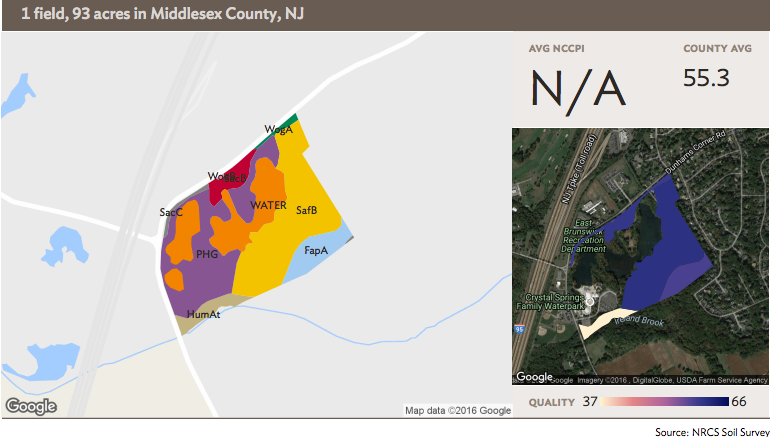

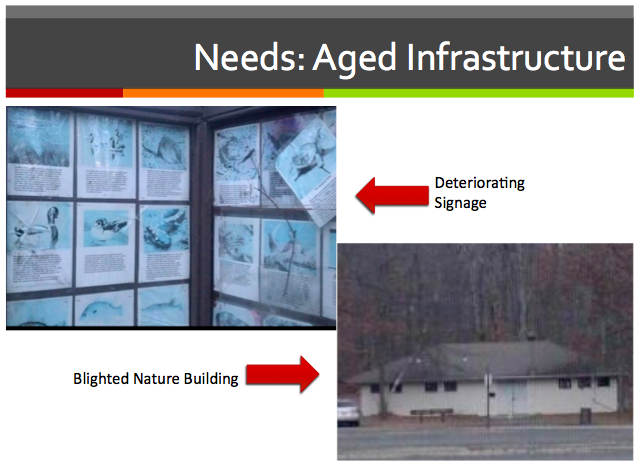

Land Assessments

Since the boundaries of the Act were created objectively, numerous issues arose. Data regarding property lines, land value, or mathematical equations were not incorporated. The area within the Act was drawn on a map and then enforced. Thus the authors of the Act neglected to physically inspect the lands. Since this Act bans “major development on hundreds of thousands of acres in northwestern New Jersey.”(Conner, 2010) An assessment of land properties could have helped to incorporate financial levity. The Act covers a large region and affects many municipalities and many landowners. The absence of such assessments led to many residents loosing financial assets. The economic losses cannot even be calculated.

Many issues stem from grouping together so many municipalities from such a large region. The Act incidentally combined different ecosystems and environments together. Each municipality has very different conditions, suburban sprawl patterns, and population densities. As a result, the Act should have acknowledged these differences.

Since the Act is already implemented, such recommendations may not be technically feasible. However, since the Act is continually updated future recommendations can be made. Any land that is going to be added or taken out of the Highlands region can be physically assessed.

Alternate Funding of Transfer of Development Rights

Initial funding of the TDR program came from a $10 million capital fund. Yet TDR programs only benefit a small number of affected landowners. The TDD programs are factored from size, location, and zoning of property. Resident’s land is based market value from 2004. These market mechanisms are based on the free market and intend to be prosperous. Like most market based initiatives, alternate funding needs to be made in order to make the TDR program economically solvent.

A way to additionally fund the TDR’s in this region is a nominal water consumption surcharge. Several municipalities have proposed this tax. Municipals within the Highland’s region believe the Act’s “development controls and related costs are imposed on but a few watershed communities, while hundreds of northern New Jersey municipalities stand to benefit immensely from safer and more abundant water supplies as well as improved ratable growth opportunities.” (Borough of Ringwood, 2005) This is a recommended policy because it is practical and feasible.

Improve Transportation Infrastructure

Since this Act greatly affected land-use within the region, transportation was also affected. Suburban sprawl was halted, promoting high densities in other regions. In addition, since receiving zones are going to receive transferred growth from the preservation areas, transportation accommodation must be made. An increase in transportation infrastructure will be needed. This will be needed in order to maintain population growth and density.

Roads and connectivity could be subsidized and maintained. More parking lots could be added to popular destinations. Public transportation can be redeveloped and emphasized. Also, transit oriented development can be promoted. While continually updating transportation infrastructure and decreasing suburban sprawl, municipalities can better aid their residents.

Redevelopment Promotion

The Act takes a lot of land from people and makes their land unusable. The government has to provide compensation and economic liquidity. This economically affected so many residents and landowners. Therefore, the Committee should promote redevelopment. Redevelopment of central business districts and depreciating areas should be promoted.

The TDR program will dramatically increase population in the receiving zones. These areas should be of concern. Whether residential or commercial, strategies will need to be included to accommodate newfound growth. Land uses will change. Strategies like mixed-use zoning will be necessary.

Amend Planning System

The idea of changing the planning system of the Highlands is another option. Fifteen members currently govern it. These fifteen members include “public officials and citizens from the Highlands region, as well as representation from both major political parties.” (Rutgers 2011) More municipal or state representatives could be added. Also a group of farmers could be added to the Committee to increase their voice in matters. This option failed to gain traction in the Doherty-Karrow Highlands Improvement Act of 2006 (A2915). However, it is still a potential recommendation.

Works Cited

ANJEC. (2010). “New Jersey Highlands.” Association of New Jersey Environmental Commissions. Retrieved April 5, 2011 from http://www.anjec.org/NJHighlands.htm

Borough of Ringwood. (2005). Resolution Number 2005-222. Retrieved April 24, 2011 from http://www.ringwoodnj.net/content/100/124.aspx

Garretson, Craig. (2011, January 25). HDC Bank to Consider Third Round Offers [Press release]. New Jersey Highlands Council. Retrieved April 20, 2011 from http://www.highlands.state.nj.us/njhighlands/news/pres/hdc_bank_012511.pdf

Hasse, John. (2003). Analyzing Urban Sprawl in New Jersey. Department of Geography and Anthropology, Rowan University, Glassboro, NJ. Retrieved April 26, 2011from http://users.rowan.edu/~hasse/

Highlands TDR Extension Bill of 2010, A602/S80. (2010). Retrieved April 16, 2011, from http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2010/Bills/PL10/7_.HTM

Highlands Improvement Act of 2006, A2915. (2006) Retrieved April 16, 2011 from http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2006/Bills/A3000/2915_I1.HTM

Horowitz, Ben. (2011, April 3). “N.J. Highlands Council Continues Approving Towns’ Development Plans, Despite Vacant Seats, Criticism.” The Star Ledger. Retrieved April 25, 2011 from http://www.nj.com/news/index.ssf/2011/04 /nj_highlands_counci l_continues.html

Kasharian v. The Highland Act of New Jersey, 2009 U.S.S. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 3078. (2009)

Lockwood, Jim. (2010, April 22). “N.J. Highlands Group Urges Christie to Protect ‘Drinking Water for 5.4 Million People.” The Star Ledger. Retrieved April 25, 2011 from http://www.nj.com/news/index.ssf/2010/04/nj_highlands_group_urges_gov_c.html

New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station (2011). “Summary of the New Jersey Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act.” Rutgers University. Retrieved April 20, 2011 from http:najes.rutgers.edu/highlands/

NJ DEP. (2011). New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Web Site. Retrieved April 25, 2011 from http://www.state.nj.us/dep/

NJ DEP. (2004). “DEP Guidelines for Highlands Water Protection and Planning Act.” NJ Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved April 4, 2011 from http://www.state.nj.us/dep/highlands/index.htm

New Jersey Executive Order No. 114 (2008). Retrieved April 17, 2011 from http://www.njhighlandscoalition.org/PDF/EO114.pdf

New Jersey Highlands Council. (2007). New Jersey Highlands Council Web Site. Retrieved April 25, 2011 from http://www.highlands.state.nj.us/njhighlands/

New Jersey Highlands Council. (2008). Highlands Regional Master Plan. Retrieved April 4, 2011, from http://www.highlands.state.nj.us/njhighlands/master/rmp/final /highlands_rmp_112008.pdf

New Jersey Highlands Council. (2010). Highlands Transfer of Development Rights Program Overview. Retrieved April 20, 2011 from http://www.highlands.state.nj.us/njhighlands/master/tdr/tdr_over.pdf

New Jersey Meadowlands Commission. (2010). “History of the Meadowlands.” New Jersey Meadowlands Commission. Retrieved March 29, 2011 from http://www.njmeadowlands.gov/about/timeline/history_F.html

New Jersey Pinelands Commission. (2007). “The Comprehensive Management Plan.” New Jersey Pinelands Commission. Retrieved April 25, 2011 from http://www.state.nj.us/pinelands/cmp/summary/#activities

O’Connor, Julie. (2010, April 27). “Farmland Owners Petition U.S. Supreme Court to Overturn Highlands Act.” The Star Ledger. Retrieved April 25, 2011 from http://www.nj.com/news/index.ssf/2010/04/farmland_owners_seek_to_overtu.html

OFP, LLC v. State of New Jersey, 395 N.J. Super. 571. (D. 2007)

Robbins, Gene. (2009, December 1). “New State Senator Michael Doherty Targets Highlands Council, State Spending.” The Warren Reporter. Retrieved April 17, 2011, from http://www.nj.com/warrenreporter/index.ssf/2009/12/new_state_senator_michael_dohe.html

Stamato, Linda. (2009, May 16). “Environmental Controversy, New Jersey Style: The Highlands Council and the NJ DEP.” NJ Voices. Retrieved April 25, 2011 from http://blog.nj.com/njv_linda_stamato/2009/05/environmental_controversy_new.html

Water.org. (2008). Water Facts. Retrieved April 26, 2011 from http://water.org/learn-about-the-water-crisis/facts/

Appendix A: Timeline of Significant Events

Timeline

1969: The Hackensack Meadowlands Reclamation Act created the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission (NJMC) and the Hackensack Meadowlands Municipal Committee.

1979: Governor Byrne signed the Pinelands Preservation Act/NJ Pinelands National Reserve passed by congress

1981: Pinelands Master Plan approved

2003: Governor McGreevy assembled the Highlands Task force in 2003 to get advice on a plan that would preserve the water in the NJ Highlands Region

2004: The NJ Highlands Act was passed/establishes the Highlands Protection Fund, to provide grants to county and local government to assist in planning efforts related to conformance with the Act

2006: Doherty-Karrow Highlands Improvement Act would restore elements of home rule that had been removed by the Highlands Act and would create a board of elected officials from local municipalities to oversee the Highlands Regional Master Plan in an action that would strip a significant amount of regulatory control from the Highlands Council. However, the Highlands Improvement Act died in committee and did not reach a vote

2007: OFP, LLC v. State of New JerseyàThis case involved a challenge of the constitutionality of the Highlands Act by a Morris County developer who wanted to subdivide their property. The plaintiff argued that the Highlands Act “operates as a bar to development as otherwise permitted by law and results in a taking of OFP’s property without compensation”.

2008: JanuaryàSupreme Court Ruled in favor of the State of New Jersey

2008: September 8th Highlands Council approves the Highlands Regional Master Plan –Highlands Development Credit Bank becomes operational with the approval of the Highlands Regional Master– Governor Corzine issues Executive Order 114 that instructs the State of NJ to allocate $10 million to the Highlands Development Credit Bank

2009: Kasharian v The Highland Act of New JerseyàFarmer John Kasharian alleged that the Highlands Act was a violation of the equal protection rights granted in the United States Constitution. Kasharian’s argument was based on the dubious suggestion that the State of New Jersey’s enforcement of Highlands regulations represented regulatory action that should only fall under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

2010: The U.S. Supreme Court rejected Kasharian’s petition in June.

2010: Governor Christie signs A-602/S-80, the Highlands TDR Extension Bill gave any New Jersey municipality to serve as a voluntary receiving zone for Highlands Development Credits

Appendix B: Formulas for Calculation of Development Credits

Residential Property

UNET x KZF x KLF = HDC Allocation

UNET = Net Yield – the number of residential lots that could have been situated on a parcel of land on August 9, 2004, taking into consideration all municipal development regulations and applicable state and federal laws and regulations.

KZF = Zoning Factor – a regional adjustment factor to recognize that the value of the land varies according to the end use to which the property could have been developed.

KLF = Location Factor – an adjustment factor to recognize that per unit value of land varies by location within the Highlands Region.

Non-Residential Property

UNET ÷ KSF/USE = HDC Allocation

UNET = Permitted Square Footage – the amount of buildable area that could have been situated on the parcel of land on August 9, 2004, taking into consideration all municipal development regulations and applicable state and federal laws and regulations.

KSF/USE = Non-Residential Square Footage Conversion – a conversion factor between various types of non-residential uses recognizing differences in underlying land value associated with various non-residential uses.

Source: Highlands Regional Master Plan, Pages 358-9

The Biomimetic approach and the sustainable features implemented in The Eden Project serve as a guideline for achieving radical savings in resource efficiency.

The Biomimetic approach and the sustainable features implemented in The Eden Project serve as a guideline for achieving radical savings in resource efficiency.